RCM Managed Asset Portfolio - Trying Things for the First Time:

RCM Managed Asset Portfolio

By Christopher Chiu, CFA

February 2025

Trying Things for the First Time: From the Dutch Windmill to the NYSE to the Current Day at RCM Wealth Advisors

This past November Jeff Bezos said in an interview that one of the distinguishing features of the American financial system was that it had the best risk capital—the willingness to risk losing money to make money. He was referring to venture capital, which is the riskiest kind of capital. Yet all the investment alternatives we take for granted today had risky beginnings, and when they were first introduced, they seemed as wonky and strange as venture capital today. Practices that seem commonplace like investing in stocks and bonds were novel and took courage and had political stakes when they were introduced.

The New Government

Risk taking was present in our country’s founding. After the federal government was formed, one of the first things it did was assume all the old debt that had been amassed by the states fighting the American Revolution. To pay for all this they issued U.S. Treasury bonds for the first time.

But the practice was marginal and controversial. The issuance of federal debt to assume the states’ debt was considered novel by the young Treasurer, Alexander Hamilton. No one knew whether they would be paid back in full. The issuer, the new U.S. government, had never done it before. So, investors needed to be compensated for the risk they were taking. Treasury bonds were offered at interest of about 6% in 1790, whereas Gilt rates, interest rates for the more stable British government bonds, on average were 4%. Many of our founding fathers, in fact, were invested in the issuance of Treasury bonds if only to show confidence in the paper and the new republic.

What was novel too was that buyers and sellers wanted to find each other to trade these securities when their value started to change with fluctuations in interest rates. A table was set up under a buttonwood tree along what had been a walled street in lower Manhattan. That street was called Wall Street and the impromptu exchange the beginning of the New York Stock Exchange.

It’s often difficult to do something new for the first time. But it helps if you see someone else doing it first, whether it is buying a stock or investing in cryptocurrencies. These Americans issuing and trading their securities had acquired this practice from the British. Formerly, the Americans were British. And the British themselves had acquired this practice by observing and partaking in the practices of the Dutch.

To draw this connection more firmly, not only was New York originally the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, the British long had trade associations with the Dutch. English wool was continually being exported to Holland with its textile mills where it was spun into cloth before that cloth was imported back to the English garment factories to become finished goods. Observing the successful customs of the Dutch and the British, the new Americans could be more confident if they took on such practices, like investing in their country’s debt.

The Dutch

This finally brings us to the 16th century Dutch, one of the most resourceful people in the history of Europe and the source of many of our financial practices. That the Dutch were so resourceful was partly by necessity. The Netherlands had few natural resources—some arable land, wind, and access to the sea. Granted so little, they were willing to take risks. One aspect of their risk taking was spending for public works beyond what they could afford from their tax base. But if the public works yielded a great benefit, they would find other ways to finance it. They too had risk capital, a willingness to risk losing money to make money.

One project they came up with was the crazy idea of augmenting their national territory, not by the traditional means—going to war with their neighbors but trying something that had not been tried before—reclaiming the land from the sea. And they would execute this bold engineering plan with another bold technique from the world of finance.

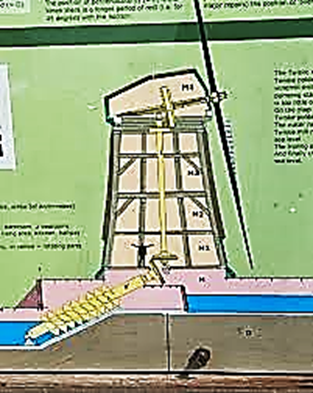

On the engineering side, the plan was to cordon off the sea with a series of barriers and dikes. Once these sections were established it would be easier to empty one section without another flooding again if a barrier failed. But how would they remove all that seawater? Where would the labor come from? As I said at the start, one resource that was abundant in the Netherlands was the wind from the North Sea. And marrying one old invention, the windmill, with an even older invention, the Archimedes screw, they invented the ability to effortlessly drain tracts of flooded area using the wind.

On the engineering side, the plan was to cordon off the sea with a series of barriers and dikes. Once these sections were established it would be easier to empty one section without another flooding again if a barrier failed. But how would they remove all that seawater? Where would the labor come from? As I said at the start, one resource that was abundant in the Netherlands was the wind from the North Sea. And marrying one old invention, the windmill, with an even older invention, the Archimedes screw, they invented the ability to effortlessly drain tracts of flooded area using the wind.

When turned by the power of the wind, the screw attached to the windmill allowed water to be ported upward over the dike and away from the lower, flooded areas. It would take years but over time, as the wind continually turned the screw, all the water from a section would gradually be drained and the tract that remained would become farmable land. The map above shows all the land that has been reclaimed by the Netherlands, section by section, using this method over the centuries. There is a Dutch saying, “God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands.”

On the finance side, the tax revenue generated from farming the reclaimed land would pay the debt incurred from the construction of these large capital projects. But the size of the initial commitment created finance challenges. It would be many years before the debt was paid back. Who would loan this huge upfront cost to get the project off the ground, locking up their own funds for years? This was the problem of liquidity.

And there was another problem, the problem of risk. Which individual entity, whether a bank or individual person, would be willing to bear the risk of financing such a large project alone? And how many of these wealthy individuals could be found if indeed one project was successful and other sets of windmills were going to be built?

The Dutch solved the problems of liquidity and risk by introducing pooled investments for the first time, where the massive loan was broken into and sold as individual units. By breaking the large loan into fungible units, each investor commitment could be as large or small as desired. No single investor needed to assume the risk of an entire project. It would be shared among as many investors as purchased the paper. Therefore, they could reach large and small investors alike. With this solution the Dutch officials could greenlight many windmill projects simultaneously because with more levels of society participating, there was much more liquidity available.

We may take it for granted, but these practices carried over from the Dutch underlie the structure of our economy. They are now commonplace. These are things we have regularly facilitated at RCM, from investing in common stocks to mutual funds to private placements in real estate vehicles. It is because of pooling and securitization that the U.S. economy can tap into levels of liquidity that were previously unattainable. This is partly why there are so many kinds of public companies today, offering an abundance of goods and services. People have many ideas but risk capital in the United States gets many of them funded and what remains are those that have succeeded.

From the Dutch perspective the lure of success is what made this massive borrowing from public markets worth the risk. The new farmable land would create a new tax base where no land had previously existed. These Dutch officials had determined correctly that this was the right opportunity for the government to borrow money because the use of public funds drew a clear line to the greater prosperity of its citizens, which would lead to more tax revenue in the future. (This is a basic but important tenet of municipal finance that the city of Chicago, its elected officials, and those who elect them should sooner remember as it struggles with its annual budgets and its creditworthiness.)